- “Growing” by Motiqua https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the problems of transitioning from a small LTO to a more medium sized ones with all of the changes that this implies. This is something which I’ve encountered fairly often in my work, but I was reminded of it specifically, when I read an article recently in HBR about tech start-ups facing the same dilemma.

You can read the article here – HBR allows you to read 5 articles for free every month if you register with the site, which is, I believe a great deal, as it is a fantastic resource

“Start-Ups That Last: How to scale your business” by Ranjay Gulati and Alicia Desantola

Tech start-ups tend to go through these organisational life cycle stages at a much greater speed than most other industries (going back to McNamara’s life cycles from my previous post, it feels like Facebook went from birth to maturity in a few months!) , but that doesn’t mean that the lessons are not applicable to our world.

The article outlines 4 key areas to be aware of and to work on in order to facilitate the transition into a more mature organisation. I’ve ordered them slightly differently from the way the authors did which reflects the importance I would attach to the 4 points as I have seen them arise in the ELT industry.

Sustaining the Culture

One of the hardest areas to deal with in such a transition is what feels – to staff – like a loss of culture. As the organisation becomes larger and somewhat more formalised something can be lost. But this shift does not have to mean that the culture is entirely changed. I would recommend sitting down with the entire team to try and work out what it is about the current culture, the “small young organisation culture” that actually does feed people and make them feel part of something, make them feel part of a family or an organisation in which their own identity is not lost. Get staff to think about why it is they do like working for the LTO, and then once you’ve got that input, work together to see how you can grow and do what needs to be done without losing what makes the place special.

I once came in as a consultant to an LTO going through this kind of change. The director felt it was time to change but also thought that the staff were against it. I talked to everyone individually and then we had an all staff meeting. From this it became entirely clear that no-one was actually opposed to the idea of growth (and in fact they felt the LTO needed to grow and expand quite dramatically as they felt they were missing out on opportunities), and everyone recognised the need for clearer procedures, but they were worried that the place they enjoyed working at would become less personal. We worked together to find out what it was that made it a good place to work and worked on what could retain that feeling and even make it better . The point here being that the director had completely misread the staff’s resistance, and in fact they were as enthusiastic and as ready as she was to start the change process.

Adding Management Structure

Perhaps one of the things that most worries everyone in a small organisation is adding more managers. Staff worry because more managers is seen a meaning more rules, and also increasing the hierarchy and putting more distance between them and those at the “top”. Managers worry because it might mean less control. And everyone sees it as taking away from the culture (see above). But if this doesn’t happen then everything will become increasingly slow moving and difficult to handle. The manager’s role is not to make rules and enforce them, the manager’s role is to support people and make sure they have what they need to do the best job they can. And one manager cannot effectively support 40 people. (yes, the manager’s job is also to make decisions, but the wider the span of control, the harder it is for that manager to find the time to make those decisions). Too much management can, it is true, mean too much bureaucracy and too much control taken away from the staff. But it needn’t, and a well handled expansion of management can be very helpful.

I worked recently with another growing LTO (it was no longer small, but was still dealing with some “small structures”) in which the teaching team had grown to about 90 people – all of whom were being managed by a single academic coordinator. Clearly that was unsustainable and a decision was taken to create teams of 15 teachers each with a supervisor who would act as team leader and report to the academic coordinator. Of course there are always difficulties in adding managers – staff might feel resentful at being now “under” someone who previously was a colleague, and the new managers can struggle to cope with that and with the change in relationships. But handled well it is essential to make the organisation function well.

Planning and Forecasting with Discipline

Small organisations tend to act on hunches, improvising as they go. What makes a small organisation successful is the ability to be flexible and quick in responding to ideas or possible opportunities. And at the same time, choosing to launch a course that doesn’t take off is not likely to be the end of the world. We feel we know the market, we have ideas about what people want and we can build courses and services that meet those needs. But as we grow our market grows too – perhaps we consider new branches or satellite schools (the example above under sustaining the culture, was one such), and perhaps we stop being experts in our possible customers. Also, many small LTOs don’t keep good records. Files have built up in haphazard ways and we simply don’t really have the data we need to make informed decisions.

One need of the sustainable LTO, then, is to start being a little more organised with the information you collect. Student feedback. Where applications are coming from. Where applications are not coming from. And to create better and more effective processes for making plans for the future. People need time for that, time to gather information, time to share it properly and time to use it as the basis for future directions. It may feel less flexible, less nimble, but once the organisation reaches a certain size making up new courses on the fly is no longer helpful . You need more clear goals and a more sustainable way of reaching them.

Defining specialised roles- generalists vs domain experts

At the beginning, as mentioned in the previous piece, everyone does everything. Teachers also answer the phones, enrol students, clean classrooms and teach every class that comes up. We are jacks (and jills) of all trades. And in small organisations this works very well. But it does mean people having to quickly and efficiently acquire new skills – often with a very steep learning curve. So as the organisation gets larger we tend to specialise a lot more. One person is responsible for answering the phones, and teachers just get on with teaching (for the most part). And then people start to be hired from outside to take care of specific functions. The LTO starts to attract a lot of young learners, and so you hire a YL expert. And away from the classroom, you might hire a marketing expert. There are many benefits with this – the YL teacher can spend her time teaching the YL classes and perhaps even training up others. She brings her specialised knowledge to the area and this can only be beneficial. It also allows those not specialised in this area to be freed up to do other things. But as you can see, often these specialised posts are filled from outside, which can leave long serving staff (the generalists) feeling rather marginalised. A sense that is only exacerbated when the organisation starts becoming more departmentalised, and the YL expert becomes the head of the YL department.

It’s important to bear in mind that the generalists also offer a lot to the organisation – they are the history, they know how things function and they cross different areas. If you do not recognise and accommodate this hugely important aspect of the organisation, you risk losing them, and ultimately you will end up with a very silo-ised organisation in which everybody just functions in their own little narrow piece of the puzzle. So, build relationships, use the cross-departmental knowledge and skills of the generalists to ensure continuity and an organisation in which there are not only experts in specific fields but experts in the organisation as a whole, experts in working across departments. Find ways of supporting and recognising the generalists, and work to stop the LTO becoming a series of silos.

In some respects any organisation that is growing and indeed shrinking) is experiencing some of the issues associated with scaling as referred to here and in the previous post, so even if your LTO seems larger and more established than one experiencing growing pains (or if your LTO is still young and small), it’s still worth bearing these things in mind. After all, if you look at the massive tech companies that have grown up in the large few years you will see that they are doing everything they can to try and follow these principles above – from trying to break down silos to preserving the culture that made them innovative.

Introduction

Introduction

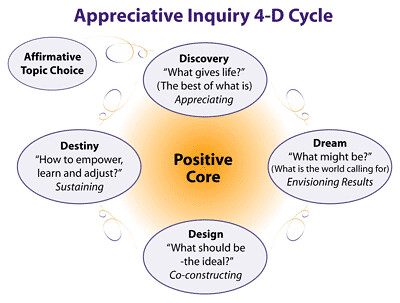

Anyway, among other things in the wide ranging discussion on ways to support teachers and managers in this current pandemic situation of emergency remote teaching, Sarah talked about how to give feedback to teachers in this period and she mentioned the idea of “Appreciative Inquiry” as a potential method for this. Soon afterwards, I was training a course for department heads on “remote leadership of teaching teams”, and as a group we discussed teacher observation and feedback. I had heard of appreciative inquiry before, through a webinar that LAMSIG had run earlier in the year presented by Ralph Rogers on the use of appreciative inquiry for change management (

Anyway, among other things in the wide ranging discussion on ways to support teachers and managers in this current pandemic situation of emergency remote teaching, Sarah talked about how to give feedback to teachers in this period and she mentioned the idea of “Appreciative Inquiry” as a potential method for this. Soon afterwards, I was training a course for department heads on “remote leadership of teaching teams”, and as a group we discussed teacher observation and feedback. I had heard of appreciative inquiry before, through a webinar that LAMSIG had run earlier in the year presented by Ralph Rogers on the use of appreciative inquiry for change management (

In the last post here I talked about

In the last post here I talked about  One of the key skills of any manager is delegating tasks. I’ve yet to meet an academic manager who doesn’t realise the value of delegating tasks, but have also met very few who actually do it as much as they should.

One of the key skills of any manager is delegating tasks. I’ve yet to meet an academic manager who doesn’t realise the value of delegating tasks, but have also met very few who actually do it as much as they should.

Many years ago, I encountered a participant on the

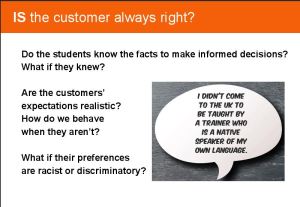

Many years ago, I encountered a participant on the this point forward, if anybody who has responsibility for recruitment says in one of my sessions “We have to hire native speakers, because the students expect/want it”, I will respond as I did back then, that even if that is 100% true it’s not a good enough answer. I am also going to see how I, in my various strands of work, can support

this point forward, if anybody who has responsibility for recruitment says in one of my sessions “We have to hire native speakers, because the students expect/want it”, I will respond as I did back then, that even if that is 100% true it’s not a good enough answer. I am also going to see how I, in my various strands of work, can support